Roman troops on a conquest campaign, the German Emperor on his way to see the Pope, aristocrats on grand tours, travelling salesmen, scholars, explorers and naturalists – all experienced South Tyrol on their journeys between Europe’s north and south. This small alpine country can thank such visitors for the part they played in the development of its rich culture and identity.

South Tyrol’s geographical location made it not only a special place of transit, but also a geopolitical pawn between empires and nations. Hence, today it is a land of contrasts – between north and south, mountain and valley, lifestyles, languages and cultures – and thus has a powerful allure for European travellers. When the fruit trees blossom in Vinschgau in early summer, while icy mountain peaks touch blue skies and grapevine tendrils curl over elegant art nouveau façades, and there is Alpine-Italian fusion cuisine to be enjoyed, it’s hard to imagine a sweeter spot on Earth.

Small excursion: In no other area is there a higher density of Pretty Hotels, a total of 16 houses from South Tyrol belong to the Pretty Hotels family.

Yet, despite all the beauty that we associate with this holiday destination, the route through South Tyrol for wayfarers of earlier centuries was not without exertion and danger. Those who wanted to get to the next valley had to take on the rugged, perilous world of the mountains. Even in the early days of human settlement, when the slopes of the Alps were still densely forested, the many passes and saddles where passage between the peaks was easiest were regarded as essential supply routes for hunters, gatherers and traders.

After the Romans built the Via Claudia Augusta as a route via Bolzano and Merano and the new Reschenpass and also occupied the Brenner Pass to the north, commercial travellers chose the narrow, steep mule track over the Stilfser Joch even then. Via the Umbrailpass, which branches off from the south ramp just below the pass summit, one reached the valleys of present Val Mustair, the beautiful valley in Switzerland.

In 1812 – the Kingdom of Italy was ruled by Napoleon at this time – the head of the Adda Department, Filippo Ferranti, began surveying a possible route from Bormio up to the Stelvio Pass. Ferranti had a three-and-a-half-metre wide road with a gradient of up to 15 per cent in mind, which would, however, only have been passable with small, two-wheeled carts and pack animals.

But short after that, Napoleon fell, Europe was reorganised, Lombardo-Venetia fell to Austria – and the plans were stopped.

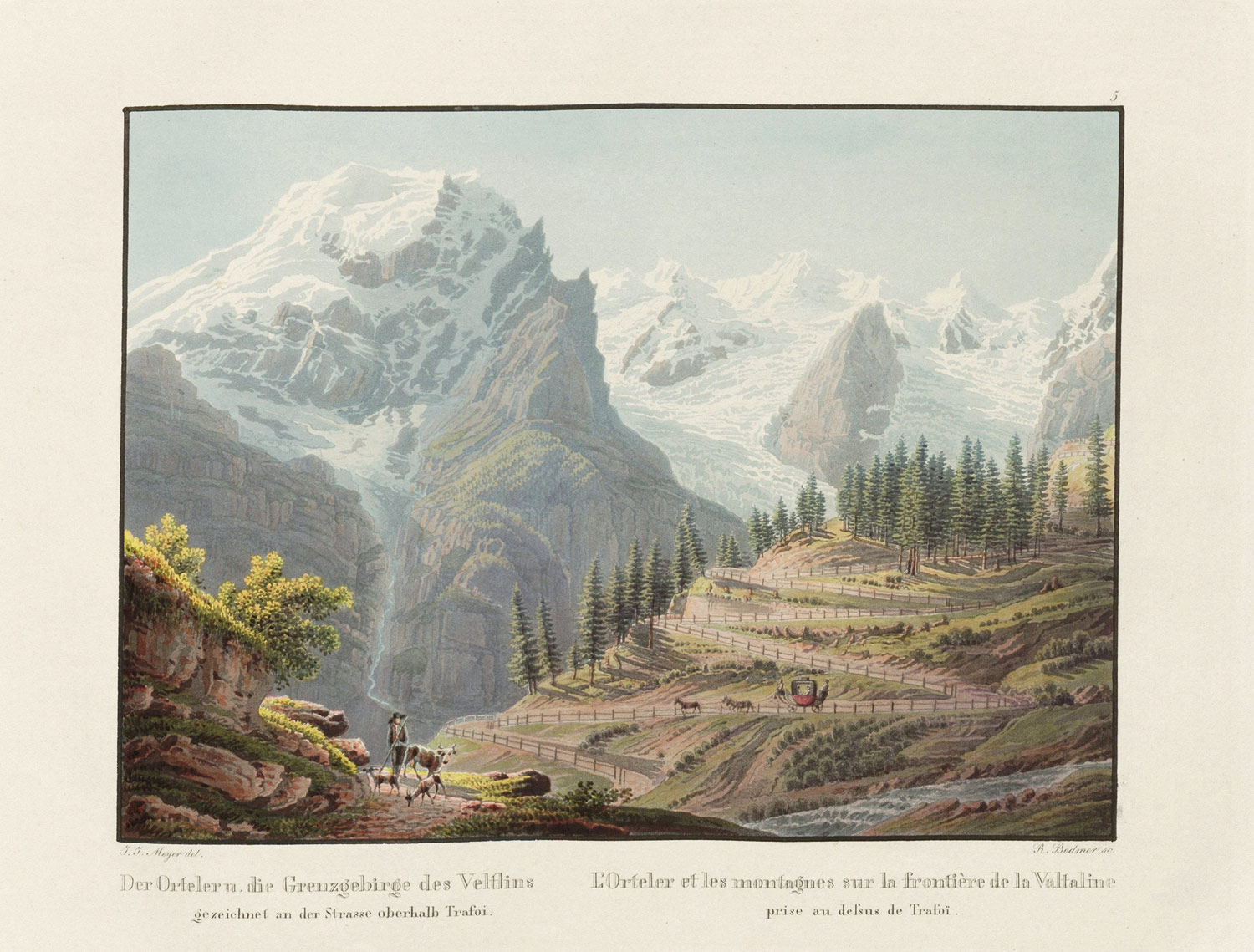

The Stilfser Joch suddenly came into the focus of the Austrian Habsburg Monarchy. In 1818, the Austrian Kaiser Franz commissioned the engineer Carlo Donegani from Brescia to develop a pass that led directly down to Bormio in Italy. In the end Donegani chose the steep descent from the yoke to Trafoi in a series of numerous serpentine bends to achieve the greatest difference in altitude on the shortest route. By late autumn 1818 Donegani had completed the terrain surveys for the entire road, and by spring 1820 the construction of the road had already begun on the southern side.

As early as August 1, 1825, postal traffic from Innsbruck to Milan was established over the Joch, and in October 1825 it was opened to traffic as an important trade link between Tyrol and Lombardy.

Around 1865 Alpine tourism began in the new border region of Tyrol. Improved roads, Europe-wide train connections as well as a dense network of guesthouses and hospices created a real tourism boom in the mountains from the mid 19th century.

In the travel descriptions of that time, the mountains were no longer feared and crossed as quickly as possible; instead they were admired and enjoyed. Inspired by the spirit of romance, travellers came here to experience the pleasant thrills of the impressive natural landscape amongst the alpine peaks. Tyrol became the destination of choice for the double monarchy. Now, affluent tourists from Germany, France and England travelled in complete comfort to the spa town of Merano, taking the Tyrolean train over the Brenner, which would soon gain international acclaim as the gateway to the Alps.

Renowned researchers and alpinists also made their way through Vinschgau to the Stelvio Pass and into the neighbouring Val di Solda, which quickly became the base for mountain tourism in the Ortler massif. Many of the now legendary mountain huts were also built during this era. And the Stelvio Pass Road was again maintained, with a road toll introduced to finance the work.

The new alpine hotels

While the pass roads served as gateways to the climbing routes for ambitious mountaineers, most travellers were happy to simply gaze in wonder at the impressive mountain panorama from the comfort of a carriage seat. For this new clientele, who were keen to experience nature at its purest but didn’t want to forgo their creature comforts, the first Grand Hotels were built in the mountains around the end of the 19th century. The Greek-born tourism pioneer Theodor Christomannos, whose luxury hotel at the foot of the Stelvio in Trafoi would outshine even the noblest residences in Paris and London, played an important role in the development of tourism in Tyrol. The first visitors marvelled at the hotel’s electric lights, steam heating system, bathrooms on every floor, large dining rooms, bakery, post office, telephone and telegram facilities, dark room for photographers, in-house doctor including a pharmacy – and even a hotel orchestra. Among the guests, aristocrats mingled with industrialists and well-to-do citizens. The Vienna physician and founder of psychoanalysis, Sigmund Freud, stayed at Trafoi at the end of the 1890s – it was here that he threw himself into his essay The Psychopathology of Everyday Life.

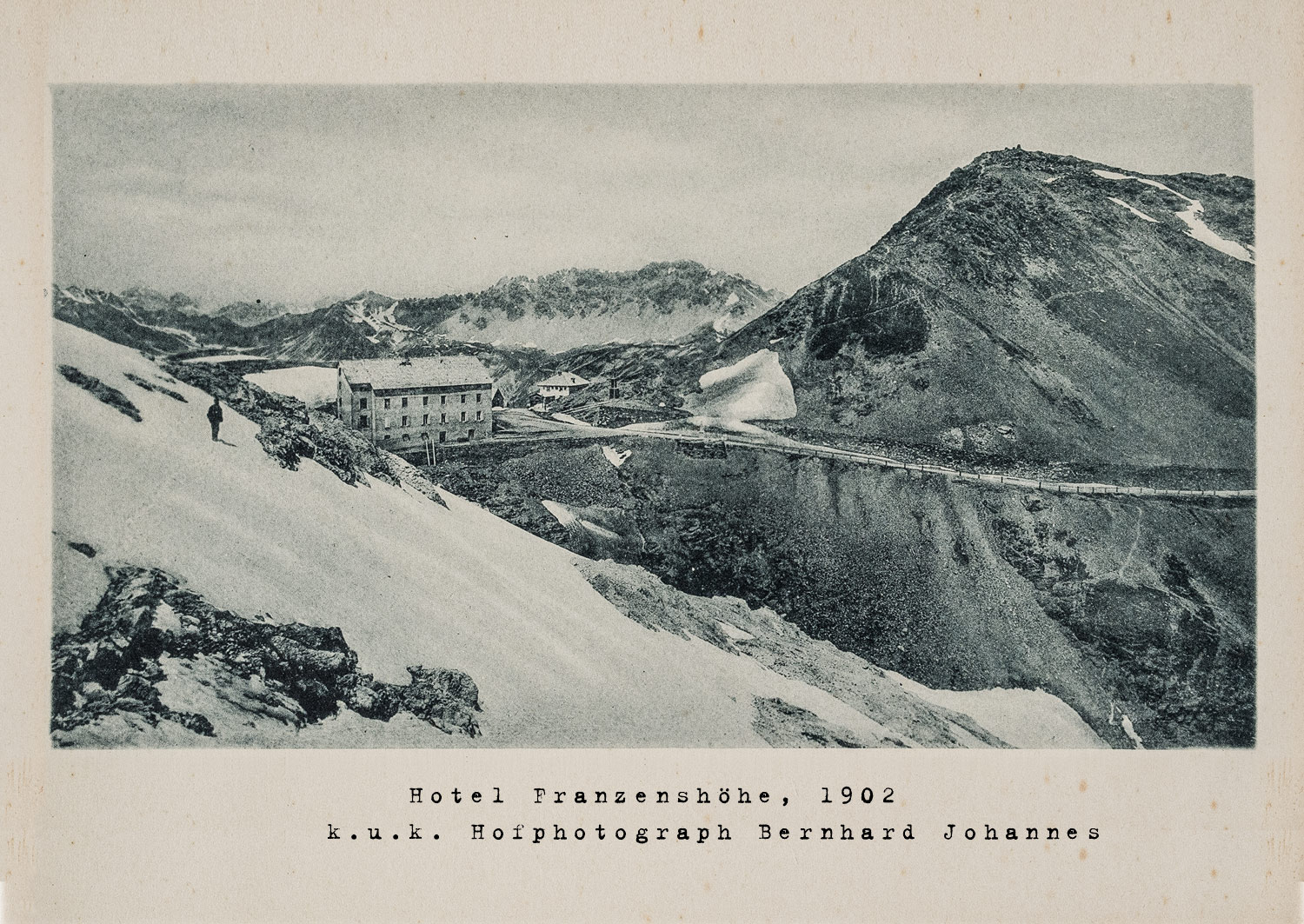

In 1890, there were only two guest houses in Trafoi – the Alte Post and the Hotel zur schönen Aussicht. By the summer of 1907, travellers en route to the top of the pass could choose from 10 hotels with a total of around 800 beds. The first large inns also appeared at the Stelvio Pass. In 1897, the postmasters of Prad built the Hotel Ferdinandshöhe at the summit (it was eventually renamed the Stilfserjoch-Hotel). At the Dreisprachenspitze on the border with Switzerland, the innkeepers of the postal hotels in Glurns and Prad opened the Dreisprachenspitze Hotel, in 1904. From then on, the postal station at the Franzenshöhe was managed by the postmasters of Spondinig, and eventually the Wallnöfer family. The current host, Karin Wallnöfer, is now the fifth-generation owner and manager of the Franzenshöhe.

The 20th century

Although there were easier routes to the south in the 20th century, the pass gained further importance with the invention of the car. As early as the 1930s, Ferry Porsche had been spotted conducting Alpine test runs at the Stelvio with the Volkswagen W30 prototype. In the late 1950s, the brakes of the latest Porsche 356 were pushed to the limits of what they could withstand through the hairpins and in the snow of the Passo dello Stelvio. And the brochure images of that time also showcased the latest sports cars on the Stelvio’s tight and twisty serpentines. Inspired by motor racing and advertising, more and more motorists flocked to the Stelvio Pass to flaunt their cars and show off their driving skills. It was getting crowded in the curves.

The Skiers

From the 1960s, there was a summer skiing boom. There were 13 ski schools around the Stelvio Pass region, in which somewhere between 150 and 200 ski instructors were kept busy over the entire summer. While Germans were discovering the Italian beaches, for the Italians there was nothing better and nobler in high summer than to strap skis to their Fiat Cinquecento and head into a “white week”. This was undoubtedly also due to the successes of the “Valanga Azzurra”, Italy’s national skiing team. Summer skiing remained popular until the 1980s, when tennis and wind surfing became the new trend sports and the glaciers at the Stelvio Pass slowly began to empty. Today, it is mostly professional skiers who train above the pass in summer.

The Cyclists

Cyclists now also discovered Italy’s highest pass, and in 1953, the Giro d’Italia was contested over the gravel Stelvio Pass road for the first time. The inspired effort of Fausto Coppi, who beat his Swiss rival Hugo Koblet after an impressive sprint between metre-high snow walls with a 4:27-minute advantage, thrilled the press and the public. The 1953 race is still hailed today as one of the most suspenseful in cycling history. “I thought I would die,” Coppi later said dryly – and a myth was born.

The “Stelvio” soon turned into the Holy Grail of mountains for racing cyclists, and was a setting for many dramatic duels. Those who conquered the 21-kilometre, 1,500-metre ascent, through the countless switchbacks to the top of the pass at 2,757 metres, had indeed mastered the highest achievement in the saddle. The Giro d’Italia of 1965 would be remembered by the racing fraternity for a very long time. After heavy snow, the finish of this leg was relocated to the southern side of the pass. However, shortly before the finish, a small avalanche fell directly in front of the racing cyclists. The images of Aldo Moser, Egidio Cornale and their colleagues, who shouldered their bikes and ran over the snow wearing summery cycling shorts, are unforgettable.

The future of the Stelvio

The future of the Stelvio Pass An initial concept was developed under the direction of Norwegian architect Kjetil Trædal Thorsen, from the internationally renowned company Snøhetta, who headed the department for experi-mental architecture at the University of Innsbruck at this time. The basic idea was to declare the entire area around the Stelvio Pass Road an alpine “world of experience”, and encourage visitors to stop at the many attractions along the road and off the beaten track. In addition to existing facilities such as the national parks, more museums showcasing the road’s history, and the Ortler front, were planned, to inform tourists about the special history of the region – thus increasing not only the visitors’ length of stay, but also their appreciation for the national park and the road itself. To further complicate things, the South Tyrol side of the Stelvio Pass Road is under the jurisdiction of the state, while the Valtellina side is controlled by Rome as a federal highway – and Switzerland, too, was included in the project planning, as the adjoining Umbrail Pass is part of the Swiss national park. In spite of this, all parties seem to have agreed on an approach. The old fort in Gomagoi will be restored and opened up on the street side, serving as an entry point to the Stelvio Pass in Vinschgau. Additional visitor centres will be above Bormio and Santa Maria.

©Curves Magazin – www.curves-magazin.com

Words: Jan Baedecker

Photography: Stefan Bogner